Here Are the Public Media Stations Most at Risk

Plus a breakdown by state, region, demographics, and more.

Last week, President Trump signed an executive order ordering the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to halt all federal funding to NPR and PBS. As I discussed in my breakdown of the EO, the two public media networks have clear legal avenues to dispute the order, an opinion echoed by several experts.

The executive order also commands public media stations that receive federal funding to cease funding NPR and PBS “directly or indirectly.” This may seem like a concession for the hundreds of local public media broadcasters in the U.S., but I opined that public media stations should expect to lose their federal funding no matter what.

The reasons why are simple: First, the word “indirectly” carries considerable latitude. One broad interpretation is that any money sent from a CPB grantee to NPR or PBS could be considered “indirect” funding, even if the station can prove without a doubt that those funds weren’t from CPB. Second, the EO is only one piece of a multi-pronged effort to revoke public media’s public funding. Congressional bills, federal investigations, White House budget proposals, even state funding cuts are already making their way through various levels of government. Some of these actions have failed, but there’s no reason for stations not to plan for the worst.

It’s clear that federal funding is an integral part of every station’s annual revenue, so what will happen if the effort to remove that funding succeeds? And who would be most affected?

Public Media’s Most At-Risk Stations

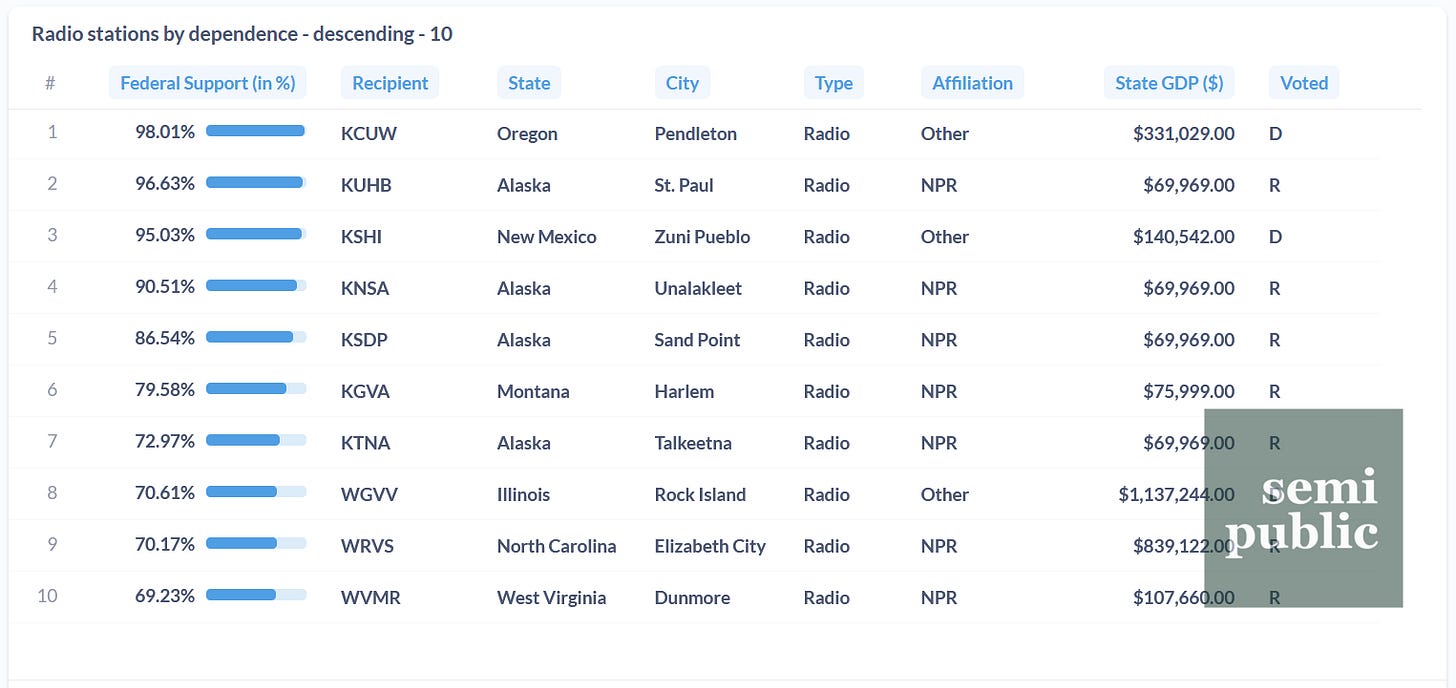

In a study of every publicly-available financial statement from FY23, I found that, out of over 500 public media stations, nine relied on federal funding for over 70% of their total revenue - all of which were radio stations. Four of those stations had a reliance of over 90%. And a majority serve Native and/or Black populations. More on that in a moment.

Here are the top ten most at-risk stations in order:

KCUW in Pendleton, OR: 98% reliance

KUHB in St. Paul, AL: 97% reliance

KSHI in Zuni Pueblo, NM: 95% reliance

KNSA in Unalakleet, AK: 91% reliance

KSDP in Sand Point, AK: 87% reliance

KGVA in Harlem, MT: 80% reliance

KTNA in Talkeetna, AK: 73% reliance

WGVV in Rock Island, IL: 71% reliance

WRVS in Elizabeth City, NC: 70% reliance

WVMR in Dunmore, WV: 69% reliance

As a reminder, here’s the (very simple) formula I’m using to calculate reliance, based on each station’s publicly-available financial statements from FY23:

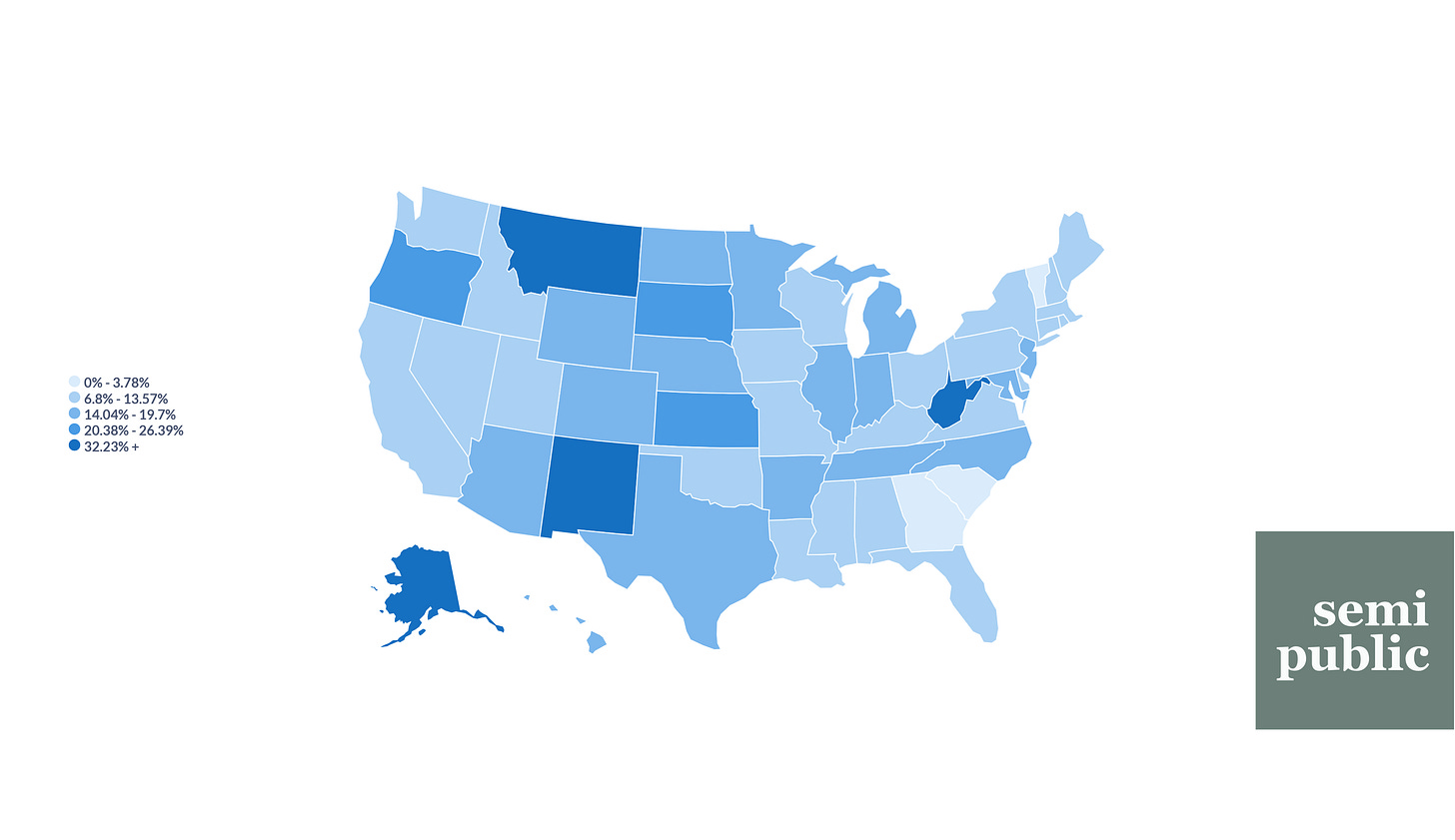

Based on our top ten list, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Alaska (36% average dependence) and New Mexico (35% average dependence) emerge as states with high dependence on federal funding among their public media stations. In fact, the map looks strikingly similar to the one I created for Current tracking per capita spending by CPB state-to-state. Except for West Virginia.

Let’s talk about West Virginia (37% average dependence) for a moment. It actually topped the ranking of states by average station dependence - not something I expected when I first started breaking the numbers down. The reason is pretty straightforward: There are only four stations that received money from CPB in the state - two from West Virginia Public Broadcasting and two from Allegheny Mountain Radio. WVPB broadcasts television and radio all across the state and has a much lower dependence on federal funding than the overall average (2% for radio and 11% for TV) while Allegheny Mountain Radio’s reach is smaller with much, much higher dependencies (69% for WVMR, which made the top ten list, and 67% for WVMS). Those four numbers added together and divided by four create the highest statewide average in the country.

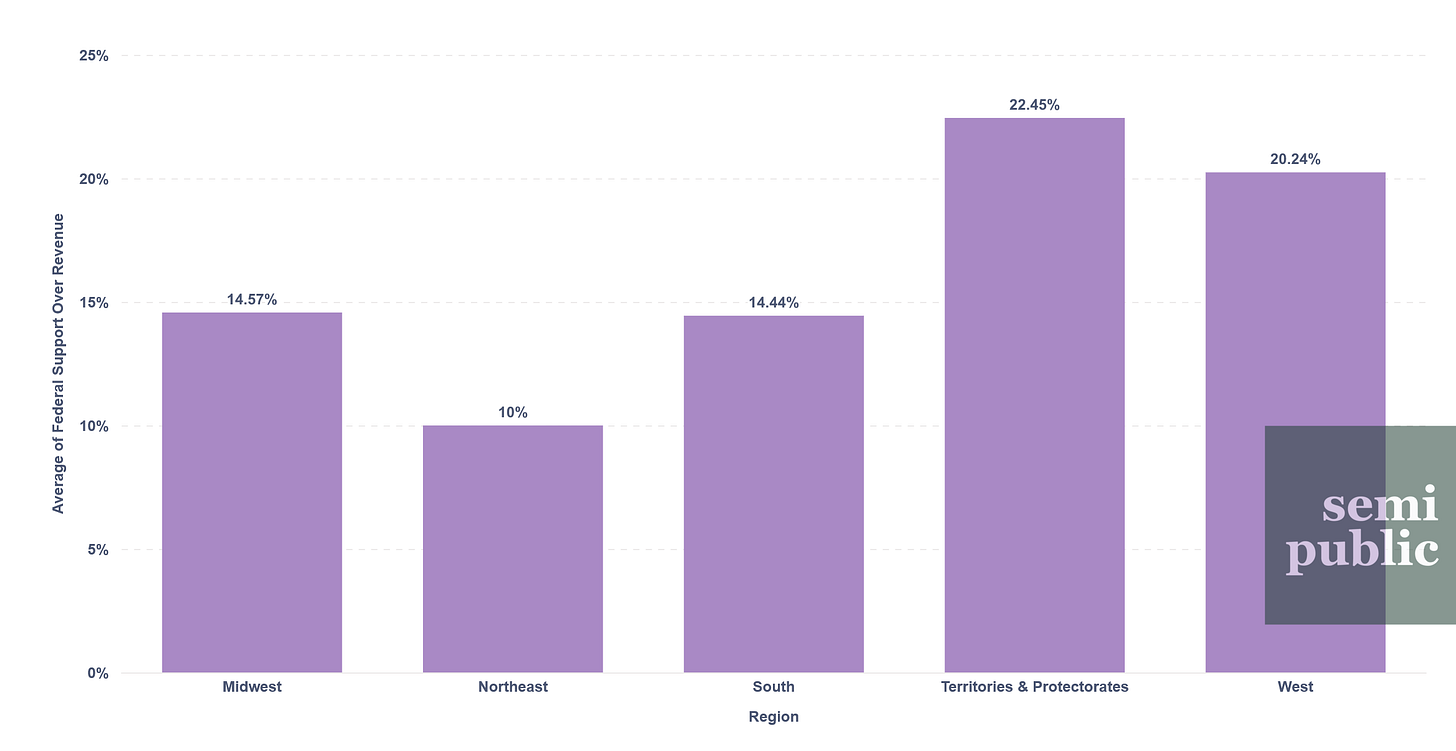

Back to the state-by-state data: Another glance at the map should make it clear that states in the Western U.S. are much more vulnerable to losing their federal funding than the rest of the country. Indeed, grouping each station by their Census-designated region shows that, among the 50 states, the average dependency on federal funding among stations in the West is nearly 40% higher than the next highest region, the Midwest. Additionally, that region is the only in the 50 states that beats the overall average, which as you may recall was almost 16%. The only region that beats the West are the country’s Territories and Protectorates.

Speaking of, there are only seven public media stations in American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Only four of these stations have financial data publicly-available and range between 14% (KGTF in Guam) and 32% (KRPG in Guam). With an average dependence of over 22%, the sudden loss of federal funding could severely diminish any public media presence outside of the 50 states.

How Will This Affect Public Media Audiences?

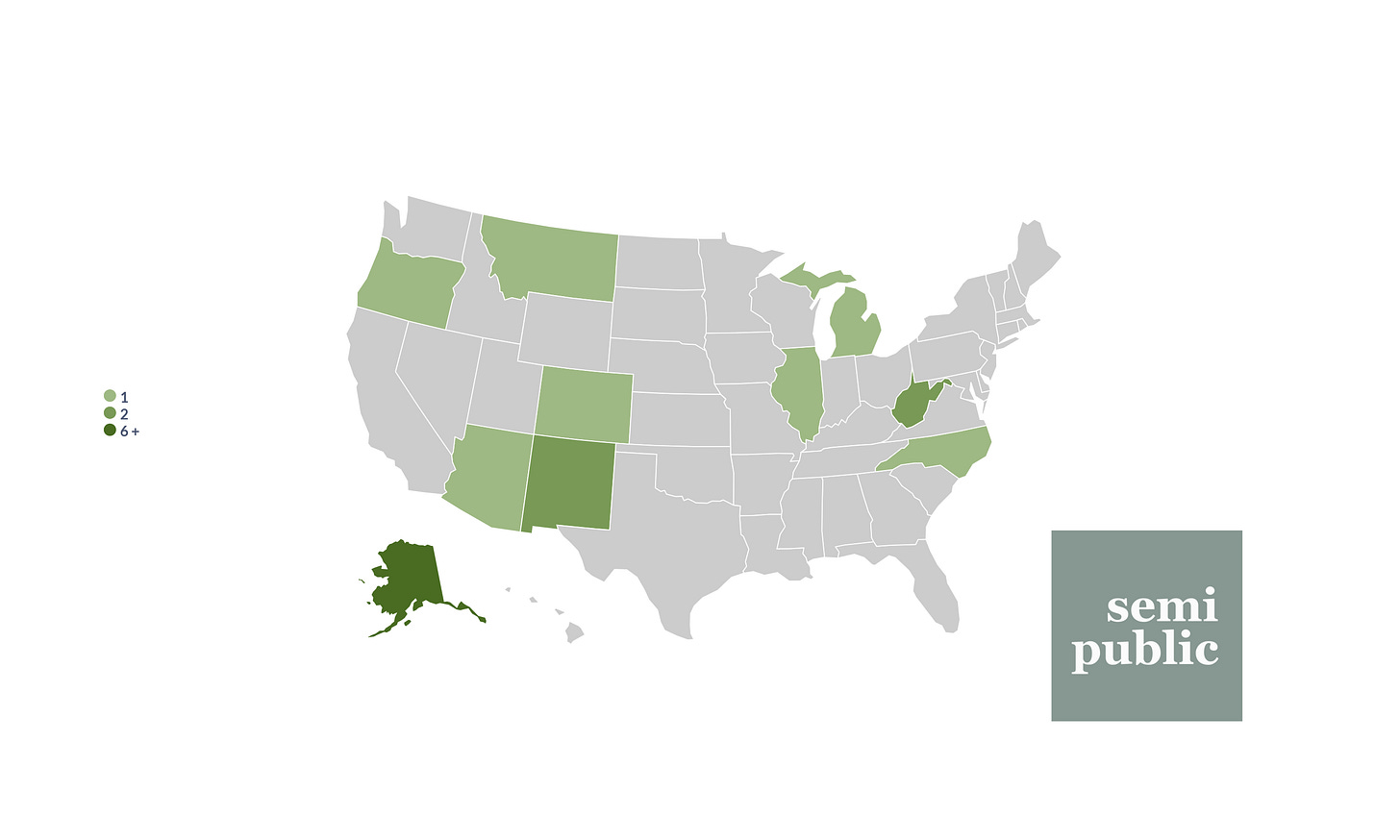

It cannot be stressed enough how devastating losing federal funding will be to Alaska as a state. If every station with a dependence of 50% or more closed following the end of federal funding for public media - which is a very generous projection - Alaskans would lose six stations, or 20% of all the state’s CPB recipients from 2023. If public media lost every station with a dependence of 20% or more, which is more realistic, Alaska would lose exactly half of all its public media stations, fifteen. As many public media advocates have pointed out since the executive order, stations in Alaskan communities satisfy more fundamental needs for their audiences than stations in other parts of the country and are therefore more indispensable.

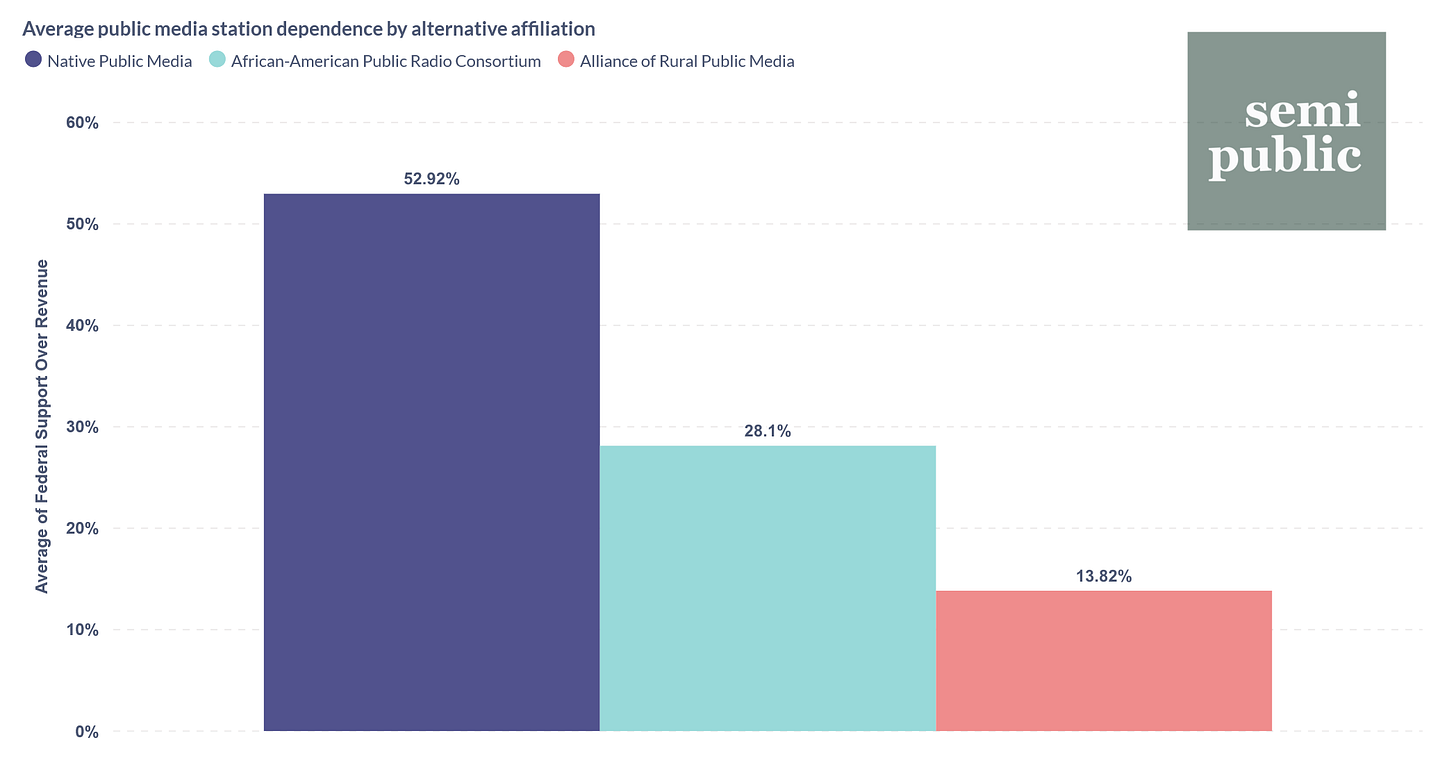

I mentioned earlier the connection between stations with Black/Native audiences and high federal funding dependence. There are a variety of complicated ways to measure race and ethnicity among television and radio audiences, but the simplest in public media is to divide stations up by their membership in special-interest alliances (in my charts I call these “alternative affiliations” to distinguish from memberships with NPR or PBS).

Native Public Media stations - several of which are themselves run by tribal governments - had an immense average reliance of over 50%. In fact, every single Native Public Media station that I had data for had a reliance of 20% or more, with the notable exception of KVCR in San Bernardino, CA. NPR’s best-case scenario for stations closing in their 2011 study was 20% reliance or more; there is no doubt that these audiences will suffer following the end of federal funding for public media, either through station closures or severe expenditure cuts.

Stations affiliated with the African American Public Radio Consortium, now 25 years old, had an average reliance of 28%: Lower than Native Public Media stations, but higher than the overall average. Thankfully, only about half of these stations had a reliance of over 20%, though there were a handful at the very top of the spectrum.

It should be noted that stations in both AAPRC and Native Public Media do not necessarily serve majority Black and/or Native communities, so when we discuss the audience impact of funding cuts through this lens, we’re only making assumptions based on how those stations self-organize.

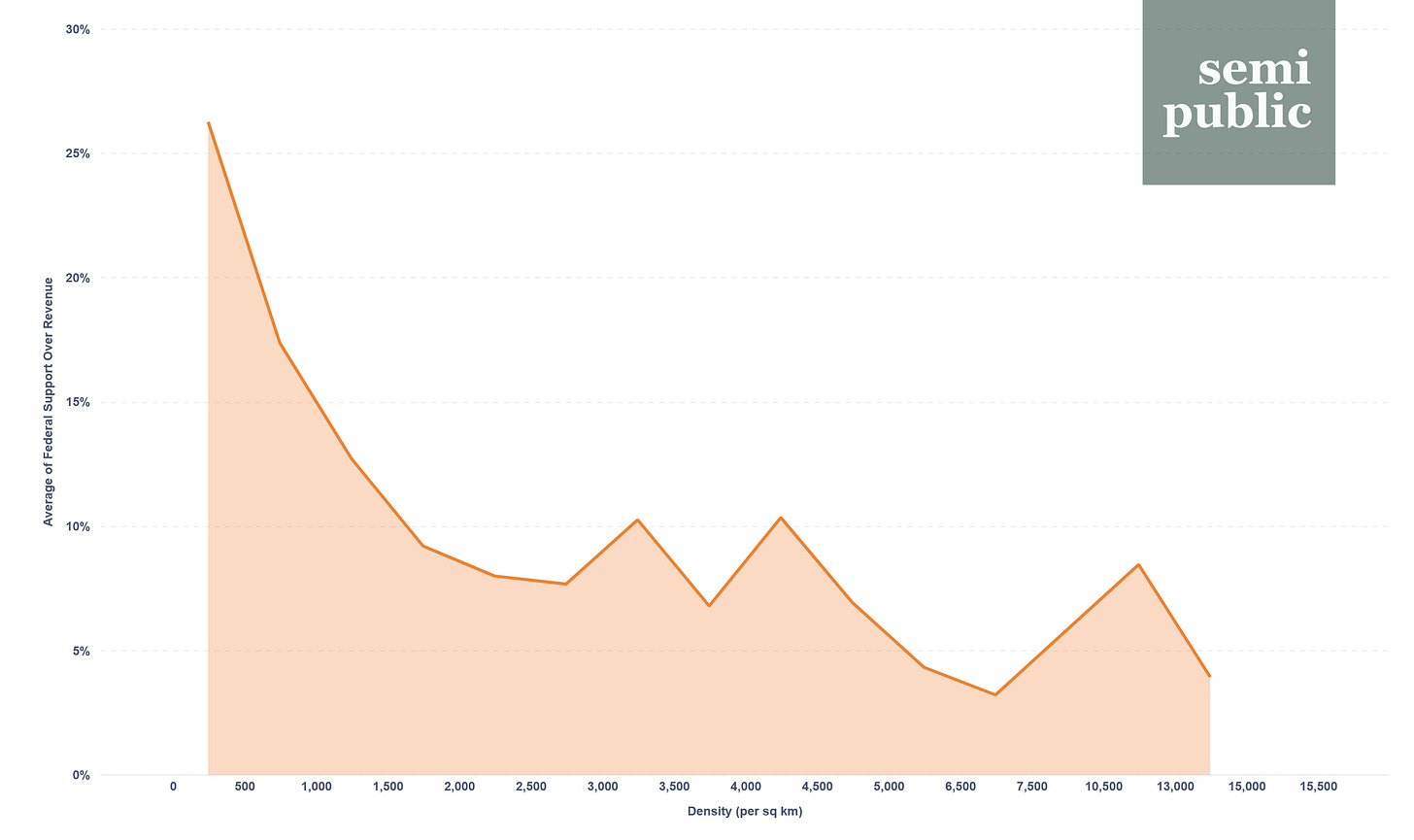

Case in point, the Alliance of Rural Public Media. We can prove, by comparing the average reliance of public media stations to the population density of the towns and cities in which they’re based, that stations in rural areas rely more on federal funding than stations in dense urban areas. Stations affiliated with the Alliance of Rural Public Media, however, have an average reliance on federal funding that’s lower than the rest of the public media system: 14%. As the alliance explains on their website, its member stations can be designated as rural by CPB, but can also merely serve a rural population. Alliance of Rural Public Media stations range from the Chicago giant WBEZ all the way to Elizabeth City, NC’s WRVS, number nine on our top ten list.

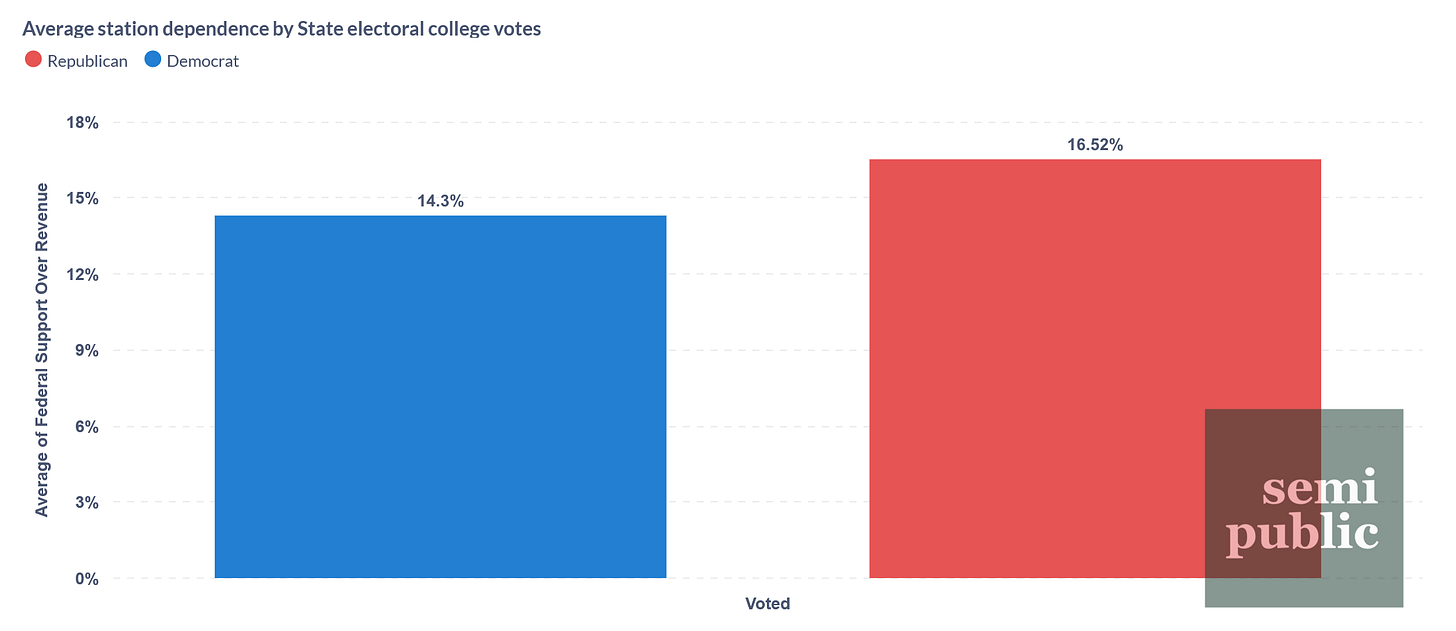

Finally, because we’re political animals, let’s take a quick look at the average dependence of public media stations by how their state’s electoral college voted in the last election. There was a clear correlation between dependence on federal funding and regional location, specifically the Western part of the U.S., but much of that region was split between voting majority Democrat and majority Republican in the 2024 election.

Dividing stations by their state’s electoral college votes shows that public media stations in Republican-leaning states are slightly more at risk than those in Democratic-leaning states. In fact, stations in Republican-leaning states had an above average reliance on federal funding, no doubt buoyed by outliers in Alaska and Montana.

The Takeaway

In plain terms, we have identified three major indicators of higher-than-average dependence on federal funding:

Location (either Western part of the 50 states, or territory/protectorate)

Alternative affiliation (Native Public Media or African American Public Radio Consortium)

Population density

Number three isn’t surprising, but the first two should be triggering alarm bells. Public media leaders should be thinking strategically, if they aren’t already, about how to stop the collapse of these at-risk stations.

And private donors, especially those of means, should consider picking any station with an above-average reliance and donating to them (after giving to their local station, of course).

After all, we can’t really call it “public” media if these stations are allowed to fail, can we?

As always, here’s a shareable dashboard containing this newsletter’s graphs and data. If you enjoyed this article, please leave a like. It’s very much appreciated.

Alex, just became a subscriber to get to the great total list of stations and the percentages of their budgets supported by cpb. Can not seem to find it.

Great post. I gave it a shoutout over here: https://continuous-wave.beehiiv.com/p/the-lighthouse-is-falling-e097f6e3e15a35b6