Breaking Down President Trump's Public Media Executive Order

Plus, a look at how federal funding of public media works (up until now)

Late last night, President Trump issued the “Ending Taxpayer Subsidization of Biased Media” executive order. We’ll go over the specifics of the EO later in this newsletter, but what the President is essentially ordering is the halt of any federal funding to NPR or PBS (including, and especially from, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting) as well as the halt of any “indirect” funding from CPB grantees to the two networks.

The EO came as a bit of a surprise to me because, as I talked about in my last newsletter, most of the public media system was waiting on a memo from the White House revoking public media’s funding, not an executive order. I was also somewhat surprised by the legality of the rumored memo - any action altering or halting CPB needs to come from Congress, after all - but this EO provides a clear legal avenue for NPR and PBS to challenge it. More on that later.

There’s a lot to unpack here, and to fully understand the implications of the EO, we need to:

Broadly understand how federal funding flows through the public media ecosystem, and;

Examine the actual text of the EO and compare it to the letter of the law as well as recent actions concerning public media’s federal funding.

Federal Funding in Public Media: A Primer

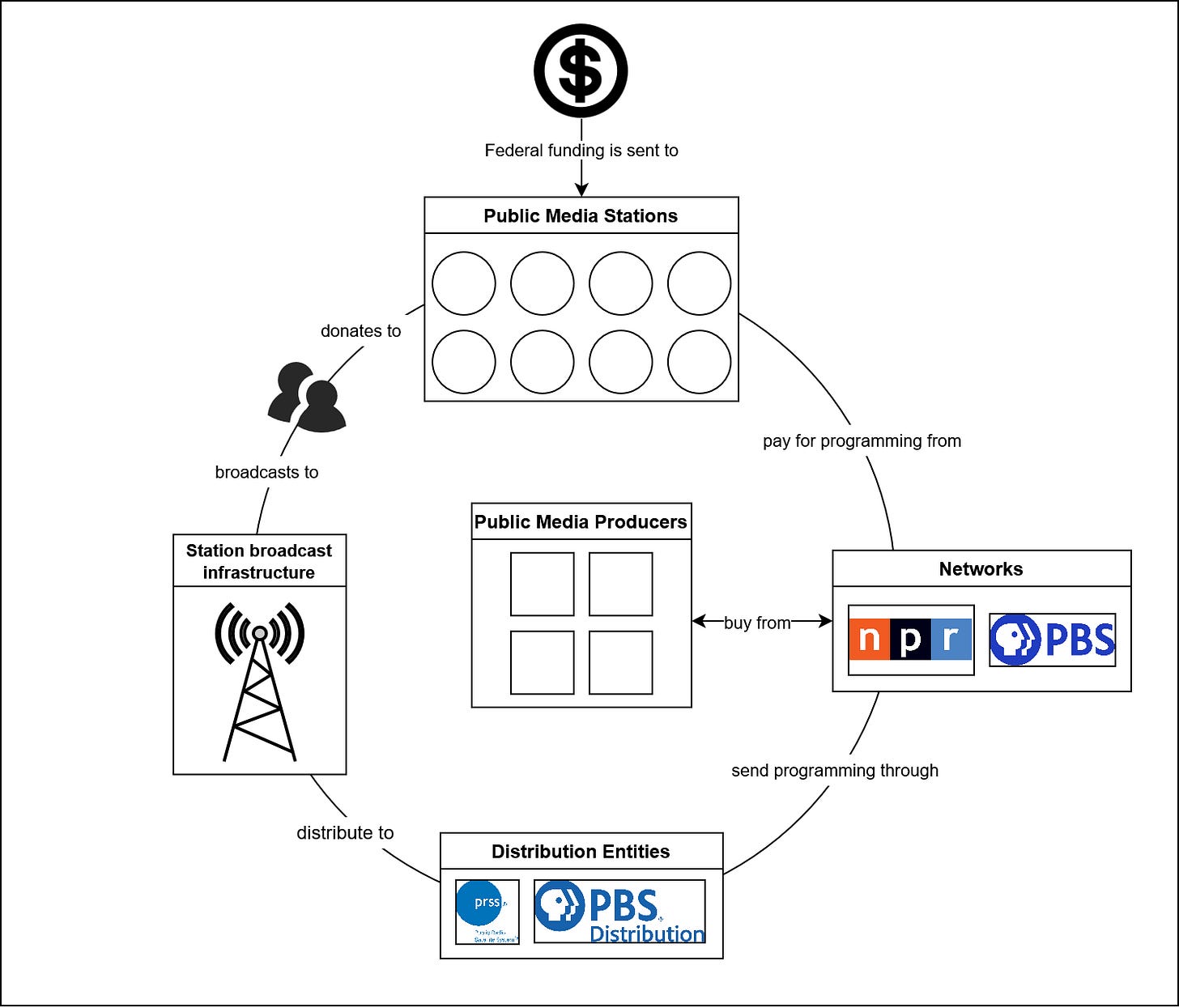

Take a look at this diagram I threw together yesterday. From a cursory glance, it should be clear why, when discussing how much they rely on federal funding, both NPR and PBS give estimates and not specific numbers: Once money begins to pass from stations to networks (and vice-versa), it enters a sort of flywheel whose inertia is maintained through a complicated series of transactions.

Let’s take a look at each step federal funding takes, starting from the top.

1. Federal Budget Reconciliation

Every year, Congress sets out to plan and pass a new federal budget. Before lawmakers start the process, however, the White House generally sends out their own recommendations and budget priorities. Often, this will include recommendations for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Once the reconciliation process has ended and the bill containing the budget has been passed by both the House of Representatives and the Senate and signed by the President (or a Presidential veto has been overridden), federal funding begins to flow. This is where public media’s federal funding starts to diverge. Most of the money that public media entities are allowed to receive goes to CPB (the next step), but other federal agencies, like the National Institutes of Health, may allocate some of their own budget for grants to support related reporting or programming initiatives.

2. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting

After receiving a lump sum of federal funding, CPB is statutorily mandated to use that funding in specific ways: Less than 5% of it can be used for administrative costs by CPB, while more than 70% must go directly to public media stations in the form of grants

There are three general categories for CPB grants: Community Service Grants, Interconnection Grants, and other specific grants that can cover anything from program production to specific initiatives.

3. Interconnection Grants

One of the lesser-known provisions of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 is to “assist in the establishment and development of one or more interconnection systems to be used for the distribution of public telecommunications services.” In fact, if you search the act for the word “interconnection,” you’ll find it mentioned at least 19 times. Another lesser-known provision of the Act is that these interconnection networks use satellite technology.

Nowadays, there are two major entities that interconnection grants are given to: the Public Radio Satellite System and PBS Distribution. Both entities have complicated ownership structures - PRSS is owned by a collective of stations and contracts NPR to run it, while PBS Distribution is jointly owned by PBS and WGBH - but it should be noted that both NPR and PBS include interconnection grants in their overall federal funding tally. We’ll talk more about how PRSS and PBS Distribution fit into the public media ecosystem later.

4. Non-CPB Federal Grants

As mentioned before stations and networks alike apply for and are given grants from federal entities outside of CPB. Mostly, these are for reporting initiatives and are only a very small part of public media’s overall federal funding.

5. CPB Grants Sent Directly to Stations

Of the three general categories of grants I identified earlier, Community Service Grants are by far CPB’s highest expenditure. These are sent directly to public media stations (after some rather intense financial scrutiny) and can be used to support anything from programming to equipment purchases. Generally, these funds are what stations use to pay NPR and PBS and comprise of these networks’ “indirect” funding.

Stations can also receive a variety of other types of grants from CPB, ranging from programming production grants, to specific reporting initiatives. I’ve placed these in their own category not because they’re not important, but because there are too many to accurately show in an already-crowded chart.

6. CPB Grants Sent Directly to Networks & Producers

When NPR and PBS talk about their direct federal funding - “less than 1%” and “about 15%” respectively - the grants I placed in the “other” category are generally what they’re referring to. Like stations, they apply for and receive funding for things like program production and specific reporting initiatives. It’s important to keep in mind that, while these make up a substantial amount of money, NPR and PBS rely more on membership fees from stations, which are buoyed by CPB’s Community Service Grants.

It’s also important to keep in mind that NPR and PBS are not the only entities that produce content for public media. In fact, PBS doesn’t directly produce its content at all, the network buys shows from stations and independent production companies. And public radio stations buy content from other producers like PRX/PRI, WNYC, and APM. Nearly every entity that sells public media programming is receiving some sort of CPB grant to aid its work.

7. The Public Media Flywheel

Despite several divergences, we’ve been able to directly trace federal funding to its source - until now. Once money enters the ecosystem through stations, producers, and networks, it enters a self-propelled flywheel whose inertia began, essentially, in 1969. This is where all public media money churns and spins.

Let’s track the flywheel from the perspective of a local radio or television station: The station applies for and receives federal funding, mostly through Community Service grants from CPB, but also other types of federal grants. That station, in part, uses the federal money as part of its membership fees to a network like NPR or PBS. Both NPR and PBS buy programming from third-party producers (though NPR less so) using station fees. That programming is distributed from the networks and producers back to stations through distribution entities like PRSS or PBS Distribution. Stations broadcast the content over the air (or by internet) to their audience, who in turn donate to the public media station. That station then uses the audience donations, as well as any new federal funding, to pay for their network fees. And the cycle continues, ad infinitum.

Every stop on the flywheel benefits from federal funding, either directly or indirectly. We know that stations, networks, distribution entities, and producers can receive direct federal funding, but federal funding alone isn’t enough to keep the lights on. That’s why inertia is so important. And that’s why “indirectly” supporting NPR or PBS gets complicated.

8. Reaching an Audience

As mentioned before, the statutory purpose of the Interconnection grants given to PRSS and PBS Distribution is to aid the distribution of public media content through the use of satellites. And that’s exactly what PRSS and PBS Distribution do: Content is uplinked to a satellite, downlinked to an antenna at a public media station, processed, and then sent to a transmitter for the public to enjoy. Satellite interconnection is a critical piece to the entire public media ecosystem.

But that’s not the only way to send and receive public media programming: A good portion is sent to stations via the internet, and stations and networks alike make their content available to the public through a variety of internet-based services. In fact, several of the “other” CPB grants are intended for this exact purpose.

The goal, of course, is to attract more donors and more sponsorships. All of this revenue, along with federal funding, is closely tracked by stations and used to apply for federal grants the next fiscal year.

The Executive Order

Now that we understand how federal funding trickles down through the public media system, we can accurately assess the written text and intent of last night’s executive order. The White House lists out its reasoning in Section 1; there is nothing new about the arguments being made, so let’s skip to the next section, where the instructions to CPB and stations begin.

Section 2(a)

The CPB Board shall cease direct funding to NPR and PBS, consistent with my Administration’s policy to ensure that Federal funding does not support biased and partisan news coverage. The CPB Board shall cancel existing direct funding to the maximum extent allowed by law and shall decline to provide future funding.

Essentially, the EO is instructing CPB to cease sending funding to NPR and PBS and revoke any future funding already allocated to the networks.

What I am immediately struck by is the clear legal pathway this provides for NPR and PBS to challenge the executive order in court. As I alluded to in an earlier newsletter, the rumored rescission memo was quite tame in comparison, as it’s clear that only Congress has the power to alter or disband CPB. Indeed, both NPR and CPB have signaled that they will be contesting the EO on these exact grounds.

There’s also a First Amendment question: Who determines what content is “biased and partisan?” The Founding Fathers certainly didn’t intend for it to be the White House.

Section 2(b)

The CPB Board shall cease indirect funding to NPR and PBS, including by ensuring that licensees and permittees of public radio and television stations, as well as any other recipients of CPB funds, do not use Federal funds for NPR and PBS. To effectuate this directive, the CPB Board shall, before June 30, 2025, revise the 2025 Television Community Service Grants General Provisions and Eligibility Criteria and the 2025 Radio Community Service Grants General Provisions and Eligibility Criteria to prohibit direct or indirect funding of NPR and PBS. To the extent permitted by the 2024 Television Community Service Grants General Provisions and Eligibility Criteria, the 2024 Radio Community Service Grants General Provisions and Eligibility Criteria, and applicable law, the CPB Board shall also prohibit parties subject to these provisions from funding NPR or PBS after the date of this order. In addition, the CPB Board shall take all other necessary steps to minimize or eliminate its indirect funding of NPR and PBS.

In its fiscal year 2024 financial reporting guidelines, CPB lays out for stations how exactly to report how their Community Service Grants were spent. In Annual Financial Reports (what the majority of public media stations fill out), that reporting is located in Schedule F and contains a total of seven expense categories. Essentially, what this subsection of the EO commands is that stations cease using CSG money, as would be reported in Schedule F of their AFR, for NPR or PBS fees.

The first reactions I saw to this Executive Order this morning (yes I was asleep at 11PM Eastern last night, I’ve got a toddler) were private sighs of relief among local station employees. This EO is specifically targeted towards NPR and PBS, after all, and it’s easy enough to report only using income from donations and underwriting for PBS and NPR fees.

But there’s a key phrase littered throughout the EO: “indirect funding.” According to this subsection, stations are not allowed to indirectly fund PBS or NPR, and CPB is commanded to take steps to “minimize or eliminate its indirect funding” of the two networks. What exactly does it mean to indirectly fund PBS or NPR? And how do you enforce that?

As we’ve seen with other executive orders and lawsuits, the White House tends to take a maximalist approach to both its executive powers and the written word of its executive orders. NPR and PBS stations should be prepared to lose their federal funding no matter what.

Section 3(b)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall determine whether “the Public Broadcasting Service and National Public Radio (or any successor organization)” are complying with the statutory mandate that “no person shall be subjected to discrimination in employment . . . on the grounds of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex.” 47 U.S.C. 397(15), 398(b). In the event of a finding of noncompliance, the Secretary of Health and Human Services shall take appropriate corrective action.

The beginning of Section 3 instructs other agencies to pull any other federal funding from NPR and PBS - not unexpected - but Subsection b is concerning for two reasons.

First is that NPR, PBS, and scores of public media stations have been public proponents of diversifying their workforces, often describing that work with the initialism DEI. One of President Trump’s first executive orders declared DEI programs “illegal and immoral.” It’s not a stretch to think that Secretary Kennedy has enough to pin something on NPR or PBS.

Second is Uri Berliner. In his article criticizing NPR, Uri makes it clear that he believed a focus on race and identity from within the network had been detrimental, singling out the formation of identity-based employee groups. He was immediately placed on administrative leave and resigned from his position shortly thereafter.

What’s concerning about the EO in the context of Uri’s piece is that it firstly gives clear context on identity-and-gender-based activities from within the network that could be an early step in establishing “discrimination in employment.” Secondly, Uri himself had a public departure from the network - could Secretary Kennedy, utilizing the Administration’s maximalist interpretations of the law, also use this as proof of “discrimination in employment?”

What’s Next?

For now, it’s business as usual within the public media system, albeit with more fundraising. I was struck this morning by a particularly effective message from my local NPR affiliate: They stated to the listeners exactly how much funding they received from CPB and used that as their fundraising goal. This is the kind of transparency I’ve been hoping for since my first Current article.

Right now, NPR, PBS, and CPB have legal avenues to exhaust. Meanwhile, public media stations that take content from NPR or PBS have three options:

Do nothing and wait for something to change, like a legal injunction.

Continue taking NPR/PBS content, but changing how it’s paid for - either by reporting the expenditures as non-CPB in their AFRs and FSRs, or by indirectly paying the networks through unaffiliated, supporting entities, like “friends” groups. This is the most obvious action, but it does put stations with a high dependence on CPB at a much greater risk than their wealthy counterparts. As I mentioned before, there’s also a high risk that the letter of the EO prohibits any CSG grantee from giving any money to NPR/PBS.

Immediately cease broadcasting NPR/PBS content. This is probably the safest action in the short term, but also the most extreme. You could probably count on one hand how many stations are big enough to actually fill their airwaves 24/7 with content that’s not from NPR or PBS. Even WNYC takes Morning Edition and All Things Considered for several hours a day. Additionally, there’s a reason why so many stations take content from the two networks: Their programming is a boon for local fundraising.

There’s a lot for public media to take in and consider. I’ve laid out where the ecosystem stands as of right now, 1:30PM Eastern on May 2nd, but as with everything in this administration, the situation will change day by day. I’ll be here for it.

As always, here’s a shareable dashboard for this newsletter’s charts.

Nice to see an actual analysis.

Thanks for this!